Duke Energy is trying to triple the mandatory fee that South Carolinian’s Duke customers pay before they use the first kilowatt of electricity. Duke Energy filed significant rate increase requests with the Public Service Commission that will: a) hit particularly hard on  poorer South Carolinians, older South Carolinians, and renters and b) discourage investments in energy efficiency and alternative energies. Duke Energy Carolinas (DEC) and Duke Energy Progress (DEP) are seeking to raise electric rates for their typical residential customer (1,000 kWh per month) by 14 percent. A large component of that is increasing the “basic facilities charge” from $8.35 (DEC) and $9.05 (DEP) monthly to $28.89 (DEC) and $29.00 (DEP).

poorer South Carolinians, older South Carolinians, and renters and b) discourage investments in energy efficiency and alternative energies. Duke Energy Carolinas (DEC) and Duke Energy Progress (DEP) are seeking to raise electric rates for their typical residential customer (1,000 kWh per month) by 14 percent. A large component of that is increasing the “basic facilities charge” from $8.35 (DEC) and $9.05 (DEP) monthly to $28.89 (DEC) and $29.00 (DEP).

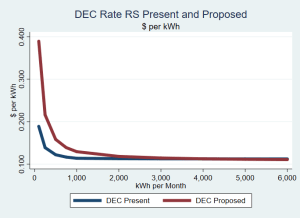

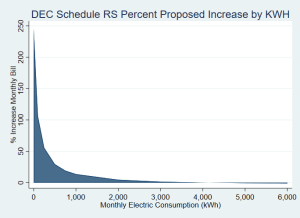

As the chart to the right shows, for DEC’s RS Rate Schedule (residential service that is not all-electric), the percent increase in monthly costs declines rapidly as use grows. T he typical DEC RS electric customer faces a 13.68 % increase monthly compared to a very high use residential customer whose bill would actually go down. The pattern is the same for DEC’s RE all-electric rate and for DEP, although the highest DEP users still face an increase, but only 3.1 %.

he typical DEC RS electric customer faces a 13.68 % increase monthly compared to a very high use residential customer whose bill would actually go down. The pattern is the same for DEC’s RE all-electric rate and for DEP, although the highest DEP users still face an increase, but only 3.1 %.

To hear the utilities tell the story, poor people are the high users because they live in energy-inefficient homes, with poor insulation, old heating and cooling equipment and use inefficient home appliances. Oh, they’re also bad consumers according to the utilities. Some low-income consumers who live in old mobile homes with ancient electric strip heating may pay more. We need to expand public and utility programs to address energy efficiency in our poor housing stock.

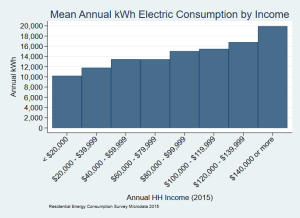

Surveys conducted by the Energy Information Administration[1] tell a very different story than the utilities—electric consumption is highly correlated to income. This graph shows us that in the South Atlantic Census Division those with 2015 household incomes up to $20,000 used only 10,219 kWh in the previous year, or 908 kWh per month. That compares to nearly twice the consumption (19,971 kWh annually and 1,660 kWh monthly) for those making over $140,000.

Surveys conducted by the Energy Information Administration[1] tell a very different story than the utilities—electric consumption is highly correlated to income. This graph shows us that in the South Atlantic Census Division those with 2015 household incomes up to $20,000 used only 10,219 kWh in the previous year, or 908 kWh per month. That compares to nearly twice the consumption (19,971 kWh annually and 1,660 kWh monthly) for those making over $140,000.

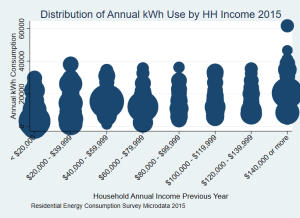

Undisputed research tells us that low-income customer s suffer from high energy burdens. That’s because their energy costs are high for their income—not because low-income consumers are high electricity users. The chart at the right shows the weighted distribution of electricity use within income groups. The highest consumers among low-income customers are lower than for all other income groups. Low-income people simply reduce electric consumption … even if it means living in the cold (or hot) and dark.

s suffer from high energy burdens. That’s because their energy costs are high for their income—not because low-income consumers are high electricity users. The chart at the right shows the weighted distribution of electricity use within income groups. The highest consumers among low-income customers are lower than for all other income groups. Low-income people simply reduce electric consumption … even if it means living in the cold (or hot) and dark.

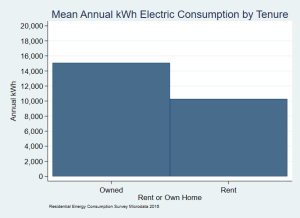

We see similar patterns if we look at renters versus owners: 858 kWh per month for renters compared to 1,257 kWh per month for owners. Consumers 65 and above used 1,062 kWh per month compared to 1,141 kWh on average for those under 65.

We see similar patterns if we look at renters versus owners: 858 kWh per month for renters compared to 1,257 kWh per month for owners. Consumers 65 and above used 1,062 kWh per month compared to 1,141 kWh on average for those under 65.

The effect of front-loading costs is that the per kWh cost declines as consumption increases. A typical DEC RS rate customer, who uses more than the average lowest-income customer, pays 12.9 cents per kWh. The highest users, who are better off, pay only 11.1 cents per kWh. And it means that our most vulnerable are paying significantly more per kWh than better off Duke consumers.

This is unjust, but it is more than unjust. Because you pay less per kWh as your consumption increases, you’re less inclined to invest in energy efficiencies like better insulation or more efficient household equipment, including heating and air. You also have less incentive to invest in alternative energy sources. While public policy should drive us to energy conservation, a front-loaded rate design sends us in the other direction.

For low-income customers, this is especially burdensome. By taking nearly $30 every month out of an already tight budget before any electricity is used, you take funds that otherwise could be used to improve energy efficiency in your home. Not only do you have a lower incentive to invest if each addition kWh costs less, a high basic facilities charges means you no longer have the money to invest in saving energy costs. You have lost control of your ability to save on electric costs.

A number of organizations will oppose these high mandatory fees. Consumer advocates will push for public hearings in the DEC and DEP service territories when hearings begin. The PSC must hear from consumers that they should reject these substantial increases to the basic facilities charge in order to protect lower income, older and renter customers and to encourage energy conservation efforts. The high mandatory fees are both unjust and bad energy policy.

[1] U.S. Energy Information, Administration, Residential Energy Consumption Survey (RECS) 2015 Survey Data (December 2018) at https://www.eia.gov/consumption/residential/data/2015/index.php?view=microdata. All analyses presented here are for the South Atlantic Census Division because the sample size does not support state level estimates. This is the most reliable data available on residential electric consumption.